How to Scale Into New Products and Channels Without Losing Buyer Trust

A playbook for CEOs and CROs to add offerings and expand into new channels without confusing payors or eroding trust.

Upward Growth provides health tech leaders with the playbooks and proof to transform complex markets into real growth. Each week, we deliver clear, practical strategies on positioning, messaging, and growth, so leaders can close enterprise deals and build repeatable momentum.

📩 Join the CEOs, GTM leaders, and investors already reading every Tuesday.

💡 Sponsorship opportunities are available: Inquire here

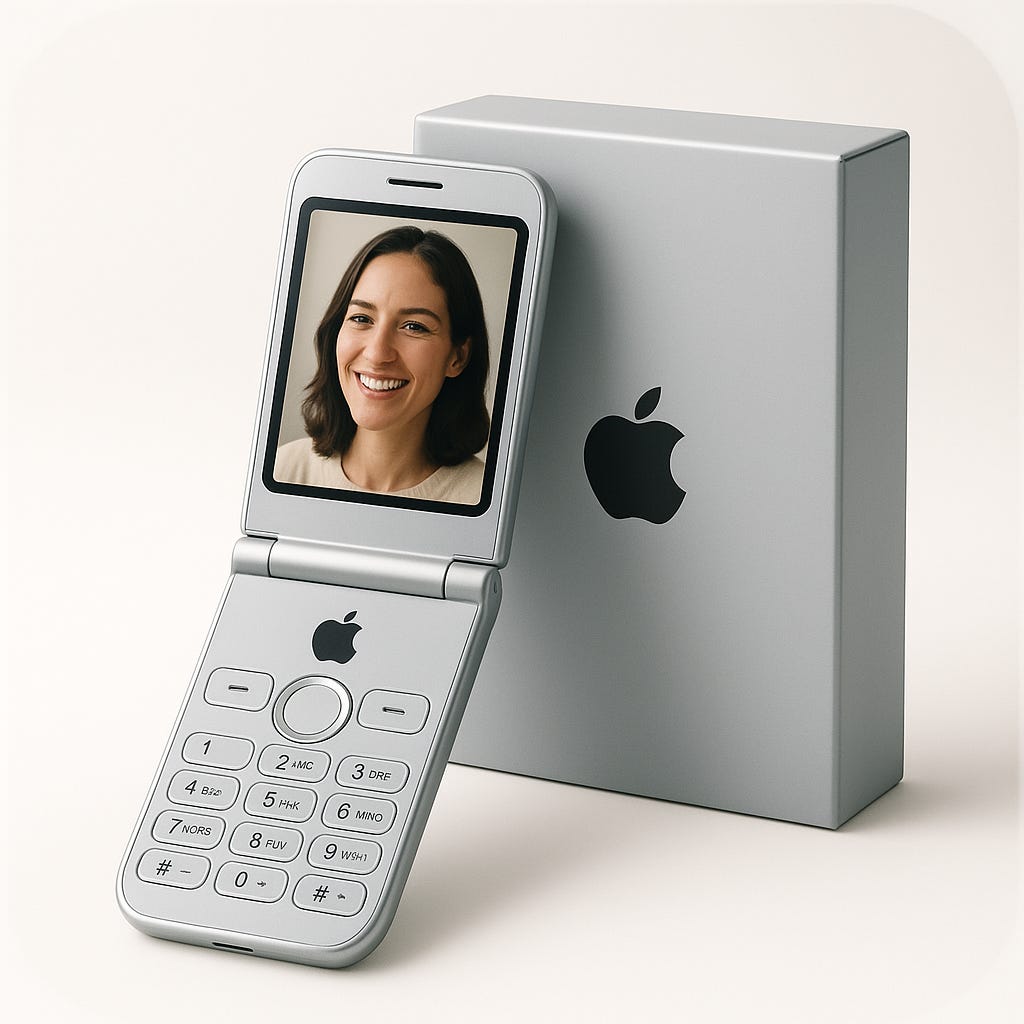

Imagine if Apple launched a budget flip phone alongside its latest iPhones. It might grab headlines. It might even appeal to a niche crowd seeking an anti-smartphone trend. But it would still land with a thud because it would feel wrong.

Everyone would immediately sense the dissonance. Not because of what the phone does, but because of what it says. It would violate the identity Apple has built for decades. People wouldn’t say, “This is a bad phone.” They’d say, “This isn’t Apple.”

That same dynamic plays out in health tech all the time, just far less visibly.

As vendors scale, they add new products, target new buyer segments, or open new growth channels. Each move can be justified on its own. Yet together, they blur the company’s core. The clear identity that once made it magnetic to buyers becomes harder to see.

Before you dismiss this as a marketing issue, understand what’s actually at stake. If you’re a CEO, CRO, or sales leader, this is not about campaigns or brand polish. It is about identity: how you are perceived in the market, how much friction you face selling your core product, and whether buyers will trust you when you introduce something new. That same perception determines whether you can break into new channels, segments, or lines of business at all.

And let’s not confuse identity with culture. This isn’t an HR item. Culture is how your people work together inside your walls. Identity is how the market tags you, your products, and your momentum (accurately or not). If you want your growth plan to be effective, you must make that identity unmistakable.

Identity goes beyond brand. It’s not a slogan or color palette. It’s the thread that connects your origin story, your product architecture, your proof, and your commercial model. It’s what gives buyers confidence that you’re built to deliver the outcome you promise.

This article will demonstrate how identity drift occurs, how it erodes buyer confidence, and how the strongest vendors expand without losing their edge. Let’s start by looking at what actually causes that drift.

How Expansion Starts Costing Deals Instead of Creating Them

Early-stage vendors usually start with a sharp edge. One problem. One buyer. One story. Everyone inside the company can recite the pitch, and everyone outside can repeat it. That kind of clarity is rare. And powerful.

As success builds, so does the pressure to broaden. Teams across the business start pulling in different directions: the product looks to add adjacent modules, sales teams seek additional personas to engage, investors want visible TAM expansion, and leadership tries to sound bigger in the market. Each move seems logical on its own. Together, they begin to chip away at the clarity that made the company easy to buy.

The clearest sign is when buyer conviction fades. You stop being the obvious choice, and every deal becomes a heavier lift (requiring more explanation, validation, and internal selling).

Let’s look at two vendors that started with a clear edge, then watched it blur as growth decisions pulled them off center:

Example 1: Member Engagement Vendor

One vendor built its reputation helping Medicare Advantage plans close care gaps and protect Stars bonuses. Their value prop was clear: targeted outreach led to documented gap closure, higher compliance, and measurable Stars bonus protection. Champions within the plan could explain it in one sentence, and executives could quickly see the financial upside.

The problems began when leadership decided that the same solution could be applied to other domains. They launched modules for HEDIS reporting, then care coordination, then utilization management. In theory, these sat close to Stars, but buyers were fuzzy on whether the vendor was offering a platform, a bundle, or just a collection of point solutions. The message about what the vendor was known for and how to buy it stopped being cohesive.

The effect was immediate. Original champions could no longer describe the vendor in a single line. Instead of saying “they help us protect Stars revenue,” they now had to choose between multiple narratives: quality reporting, SDoH programs, or utilization lift. And that stopped the story from traveling easily inside the plan.

In time, uncertainty spread. Renewal sponsors were unsure whether the next release would strengthen the product they depended on or force them into capabilities they didn’t need. At the same time, new prospects questioned whether the vendor was still built for retention outcomes or drifting into catch-all territory.

Example 2: Provider Operations Consulting Vendor

Another vendor began as a consulting shop focused on provider operations inside large health systems. Their edge was hands-on workflow redesign and operational lift. Executives trusted them to parachute into struggling service lines, find inefficiencies, and deliver results.

Over time, leadership pushed to move upstream. They launched an analytics SaaS tool to shift from labor-intensive consulting toward recurring revenue, while also targeting new markets, including payers, employers, and select pharma companies. It promised scale, but in reality, it fractured the story.

Health system clients began to question whether the vendor was still built for their problems or was pivoting to growth elsewhere. The signs piled up: project leads heard less from senior partners, account managers shifted the conversation to “the new platform” instead of next year’s operations plan, and clients felt resources once dedicated to them were being pulled away. Many started entertaining competitors who still looked committed.

In the new markets, the pitch never landed. Payers and pharma executives didn’t see a proven software company; they saw consultants experimenting with tech. Deals stalled at the curiosity stage, weighed down by the unspoken question in every room: what are you, exactly? The result wasn’t expansion. It was erosion on two fronts.

Both vendors saw logic in their expansion. Prospects and long-time clients, however, saw an identity starting to blur.

What Buyers See When You Drift from Your Core Identity

When a vendor starts looking like they’ve lost their center, plan leaders feel it, even if they can’t name it outright. In reviews, it sounds like this:

“Weren’t they the care management vendor?”

“Feels like they’re trying to be everything in population health now.”

“If we bought this, who here would actually own it?”

Those questions aren’t about features or pricing. They’re signals that your identity is no longer clear enough to defend inside the room. And once that clarity slips, executives hesitate to attach their name to you.

The difference isn’t pitch craft, it’s the discipline to embed identity into product, sales, and proof. Vendors that do it well treat identity like a strategic resource, using it to guide choices and prevent drift as they expand.

That’s where we turn next: how sharp vendors build systems to keep their edge intact as they grow.

How Companies Reinforce Their Identity as They Expand

Vendors assume growth won’t change how the market views them, yet it almost always does.

As pressure mounts to add products, chase new segments, or build new revenue lines, well-meaning teams fracture their identity without realizing it. They assume new initiatives will layer neatly on top of what already exists. In reality, they often blur positioning, confuse existing customers, and make prospects question whether the company is still built for the problem it set out to solve.

The drift usually shows up in three places:

1. Go-to-Market

Commercial drift shows up first in the field. As new segments get added, sales teams stretch the story to fit. The pitch that once had a single, sharp thesis now needs to bend depending on the room. Each variation can be justified, but the net effect is a message that no longer travels cleanly. To the team inside the company, it can feel like adaptability. To prospects, it looks like a vendor still deciding what it is.

2. The Customer’s Lens

Expansion unsettles existing clients early. A plan that hired you to streamline prior authorization suddenly hears you’re launching an employer wellness line. From your side, it’s optional growth. From theirs, it’s alignment: are you still built to solve the problem they count on you for? The shift rarely surfaces as complaints. It shows up in slower renewals, muted references, and sponsors who no longer spend capital to advance your name.

3. The Roadmap

Product drift often begins with a client request that pulls you outside your wheelhouse. A health system asks for care coordination features, or a plan sponsor wants you to manage wellness incentives. Around the same time, a national RFP is released with questions about adjacent modules. Saying yes feels harmless…until those side bets harden into obligations. Over time, the roadmap stops reinforcing the original problem you were built to solve and starts looking like a roadmap shaped by requests, not strategy. Internally, it looks like responsiveness. To buyers, it looks like a vendor without a clear focus.

Vendors who scale without losing identity handle these same pressures differently. They pilot new bets in isolation before weaving them into the main story. They build proof around their core thesis while experiments stay cordoned off. And they’re disciplined enough to walk away from short-term revenue that would cloud the authenticity they’ve worked so hard to establish.

“When identity slips, the market stops seeing you as inevitable…without a clear identity, you look interchangeable with every other option.”

Upgrade to a paid subscription to keep reading — including a full field guide on how to sequence expansion, design pilots that build proof, and give your sales team the assets to make new offerings buyable to prospects and clients in current or new channels, without diluting identity.