What I Learned Writing 50 Articles About Health Tech Growth

Reflections on one year of writing the Upward Growth newsletter

Upward Growth provides health tech leaders with the playbooks and proof to transform complex markets into real growth. Each week, we deliver clear, practical strategies on positioning, messaging, and growth, so leaders can close enterprise deals and build repeatable momentum.

🤝 Work with Ryan on payor growth strategy: Contact me

🟦 Connect with the author, Ryan Peterson, on LinkedIn.

💡 Newsletter sponsorships are available: Learn More

One year ago this week, I started the Upward Growth newsletter.

The consulting practice had already been running for over three years at that point, helping health tech companies think through positioning, sales strategy, and what it actually takes to grow in a market that doesn’t make it easy. The newsletter was an extension of that work. Both an outlet and a way to share what I was seeing beyond the clients I worked with directly.

Fifty articles later, the conversations the newsletter sparked proved more valuable than the writing itself.

Let’s face it. Health tech executives don’t engage publicly on growth challenges; not when competitors and investors are watching. Nobody’s commenting, “We’re struggling with exactly this,” on LinkedIn. But they email. They DM. They pull me aside at conferences. And in those private conversations, the same patterns kept surfacing. Different companies, different stages, different segments, but similar underlying problems.

What follows are six of those patterns. They came up so consistently this year that I stopped viewing them as isolated issues and spent time reflecting on what connected them. What I discovered is that each one is a different way that health tech companies avoid making hard choices about who they serve, what they’re willing to say no to, and what kind of company they’re actually trying to build.

These aren’t meant to be callouts. They’re meant to be useful. If you recognize your company in any of them, you’re not alone. And that recognition is the first step toward fixing it.

1. Growth-Stage Companies Are Getting Squeezed and Don't Know Why

There’s a pattern in capital flows right now that should concern anyone in the growth stage.

Recently, it’s easier to raise pre-seed funding than Series B funding, as early-stage companies are bets on potential, with investors buying a vision, a team, and a market opportunity. But once you’ve been operating for a few years, you’re a known quantity. Investors can see your growth curve, retention metrics, and competitive positioning. And a lot of what they see is ambiguity.

At the other end, very large companies with proven economics continue to attract capital because the risk is lower. They’ve figured out their model. They can show the math.

As for mid-sized companies, many grew without locking in the fundamentals (who they’re for, what problem they solve, why they win), or have grown without reevaluating themselves and now find themselves stuck. Growth has flattened, and no one can quite explain why. The usual response is to blame sales execution or hire a new VP. But often the real problem happened earlier, when the company had the chance to make hard choices about focus and chose to stay broad instead.

That choice, to delay commitment, to keep options open, compounds over time. And by the time growth stalls, the window for easy correction has often closed.

2. Positioning Isn't Marketing and the Confusion Is Expensive

When I write about positioning, those articles consistently get less engagement than my articles about sales strategy or buyer psychology. Readers see the headline, assume it’s about messaging or brand, and move on. “Marketing handles that stuff. We’re covered.”

Except positioning isn’t messaging. Messaging is what you say. Positioning is the decision underneath that, like: who you’re for, what problem you solve for them, what you deliberately choose not to do. If you haven’t made that decision, your messaging is just words. You can spend all you want on campaigns and content, but without a clear position, you’re probably not going to see the results you were hoping for.

I regularly run an exercise with clients: pull up their homepage alongside four competitors, read them aloud, and ask whether anyone can tell the difference. Most of the time, you can swap logos, and nothing feels off. Everyone improves outcomes. Everyone reduces costs. Everyone serves health plans, providers, and employers because being specific feels like leaving opportunity on the table.

The companies that break through do something uncomfortable: they choose. They pick a segment and commit to it. They identify a specific problem and orient everything around solving it. They say no to opportunities that don’t fit, even when it’s painful.

That kind of focus is rare. Which is exactly why being clear about who you’re for becomes a competitive advantage. The bar is low, but clearing it requires making the hard calls that most companies keep deferring.

3. Vague Positioning Feels Safer But Kills the Deals You Should Win

The last section was about avoiding the positioning decision, and this section is about what that avoidance costs you in practice.

Here’s how the argument usually goes:

A company stays broad in its messaging because narrowing feels risky. What if a big opportunity comes along and we’ve positioned ourselves too small? What if they need something we didn’t emphasize? So the pitch stays generic. “AI-powered platform for improving outcomes” …which could describe anyone (in almost any industry).

Sure, you may get some meetings, but here’s what typically happens next:

The health plan can’t determine which specific problem your solution solves better than the others. And so, your internal health plan champion can’t articulate why you are better than your competition. Or your RFP response blends in with every other submission. Either way, you’re stuck in limbo for months.

Months later, the post-mortem attributes the failure to long sales cycles, budget freezes, or market uncertainty. But the real problem was at the start. Either this wasn’t the right fit, or it was, but no one could tell because the positioning was too vague to differentiate.

And the long-term damage is worse. Health plans remember who wasted their time. When the next cycle comes around, the vendors who were clear about what they did get invited back. The ones who were vague might not.

Simply put, staying vague isn’t a way to keep options open. It’s a way to make sure it’s harder for your best-fit clients to never find you.

4. "AI-Powered" Stopped Meaning Anything a Year Ago

This is another version of the same avoidance, using a technology label instead of making a claim about what you actually do better than anyone else.

At some point, “AI-powered” stopped meaning anything. Every vendor uses it. Every pitch deck features it. Whatever signal it once carried has been diluted to zero.

Here’s a test I use: if a competitor achieved identical outcomes using a completely different approach, would your buyer care how you built it? Would they pay more for the AI version?

Almost always, the answer is no. They’d buy whoever gets them the result.

Saying “we use AI” is like a health plan saying “we use claims data.” Of course you do. The question is what you accomplish with it that matters to the buyer and whether you can prove it in outcomes they already track.

The vendors I see winning aren’t leading with technology. They’re leading with what the technology delivers: measurable cost reductions, quantified accuracy improvements, and specific outcomes tied to the problems health plans are already trying to solve. The AI is how they get there. But the AI isn’t the point.

Leading with a mechanism rather than an outcome helps avoid committing to a specific claim. Sure, it feels safer. But safe and forgettable often go hand in hand.

5. Warm Intros Help, But They're Not a Growth Strategy

The first four patterns are about avoiding hard choices in how you position and communicate. This one is about avoiding the hard work of building systems that don’t depend on your personal network.

Boards love this conversation. “We’ll grow through relationships.” “Our network will open doors.” “We just need the right introductions.”

And yes, a warm intro can compress trust and get you into rooms that might otherwise take months to access. In a market where attention is hard to earn, relationships matter.

But I keep watching companies use warm intros to avoid the harder work. If you can get introduced around your positioning problem, you don’t have to fix it. If every deal feels like a special case driven by a personal connection, you never have to ask whether your sales process actually works.

Warm intros feel capital-efficient (and boards love capital-efficient). But relationships don’t compound. They don’t scale. And they let you postpone building the systems that would actually allow you to grow on the merit of what you do, not who you know.

I’ve been asking for years: name a health tech company that reached $50M on warm intros alone. I’m still waiting. Referrals can supplement an engine. They aren’t the engine.

6. The CRO Role Has Become Nearly Impossible to Do Well

The previous patterns are about avoiding choices in strategy and positioning. This one is about avoiding a hard truth in how companies structure themselves, specifically the CRO, Head of Sales, etc.

Look at what the CRO role has become: sales strategy, pipeline generation, forecasting, hiring, coaching, comp design, pricing, competitive positioning, enablement, CRM operations, cross-functional alignment with marketing, product, and customer success. That’s seven or eight distinct functions, each requiring real skill and sustained attention.

Nobody can execute all of them well. But the role assumes someone should, and most CROs feel that admitting bandwidth constraints is seen as making excuses. So they spread thin, firefight constantly, and defer the strategic work that would actually fix root causes. And when growth stalls, the diagnosis is usually “we need a different CRO” rather than “we designed a job that can’t be done.”

The companies that figure this out don’t all solve it the same way. Some bring in outside help for specific areas, such as strategy or positioning. Others create internal roles that take ownership of functions like enablement or revenue operations. The right answer depends on stage, budget, and what’s actually breaking.

The common thread is honesty about what’s realistic. Right-size the role, then hold the person accountable for what they can actually do well.

7. The Leaders Who Succeed See How the Pieces Connect

The six patterns above are all variations on the same theme: avoiding commitment, deferring decisions, and hoping that staying flexible will somehow be safer than getting specific.

But there’s a related pattern I see in how growth leaders think about their own roles, and it’s why this newsletter covers topics that might, at first glance, seem outside their lane.

Growth problems don’t stay contained in the sales org. A bad implementation process shows up as churn that kills your expansion revenue. A product roadmap that doesn’t align with what sales is promising creates objections that are hard to overcome. A poorly designed compensation plan drives your top performers out the door.

Treating these as “someone else’s department” is another form of avoidance. It lets you focus on your slice without taking responsibility for how the pieces connect.

The most successful growth leaders don’t think that way. They understand how the system fits together. They read about Medicaid dynamics even when they only sell to MA plans, because regulatory pressure migrates across programs. They pay attention to commercial trends because innovations there eventually get tested in government markets.

Growth is a system, not a department. Learning to think that way doesn't happen by accident. It's a choice to zoom out, to study how the pieces connect, to care about things that aren't technically your job. Those who make that choice tend to be much more successful and (at least me personally) more fulfilled by their work.

8. We All Have Front-Row Seats to Healthcare's Failures

The patterns above are all about business: positioning, process, structure. But there’s something else I’ve noticed this year that’s harder to quantify, but is vital to try to understand.

The industry has felt very different this past year, and I’ve been reflecting on what exactly feels so different.

Many people in this industry are watching the same thing play out in their own lives. Healthcare costs are climbing so fast that working people are gambling on going uninsured or cutting their medication doses in half to stretch a prescription. Adult children spending their weekends on hold with insurance companies, fighting prior auth denials for a parent’s medication that’s worked for years. Seniors are getting discharged from the hospital with instructions that no one explained and follow-up appointments that no one scheduled. People who work in health tech every day, posting on LinkedIn about terrible care experiences for themselves or the people they love.

We have front-row seats to how broken this is. And many of us are also the ones trying to hold it together for our families while we work on fixing it professionally.

I think that shared frustration is changing the atmosphere. There’s more generosity than pure competitive dynamics would predict. More “how do we actually make this work” and less zero-sum thinking. The business pressures are real, but beneath them, there’s a layer of people who genuinely want the industry to improve, not just their own company.

Year Two and What’s Next

Upward Growth has been a consulting practice for four and a half years. The newsletter (which shares the same name) started a year ago as an extension of that work. A way to share ideas more broadly, to start conversations beyond client engagements, to see what resonated.

Both sides have grown more than I anticipated.

The consulting work had a strong year. The newsletter opened doors I didn’t expect, like podcast invitations, guest writing requests, and conversations with people I’d admired from a distance. The two feed each other: the writing sharpens how I think about client problems, and the client work gives me something real to write about.

I’m building on that in Year Two of the newsletter. More reach for these ideas. More ways to participate in the conversation about how health tech companies actually grow. I don’t yet know exactly what form everything will take, but I’m paying attention to what the demand is telling me: there’s an appetite for candid discussion about strategic growth. The kind that goes deeper than pipeline hacks and campaign tactics.

If you’ve been here for much or all of this last year, thank you. You took a chance on something that didn’t exist yet, and the responses (private and public) shaped what this became.

If you’re newer, welcome! There are fifty articles in the archives to read through!

And as always, reply if something landed, or find me on LinkedIn. I read everything.

Year Two starts now.

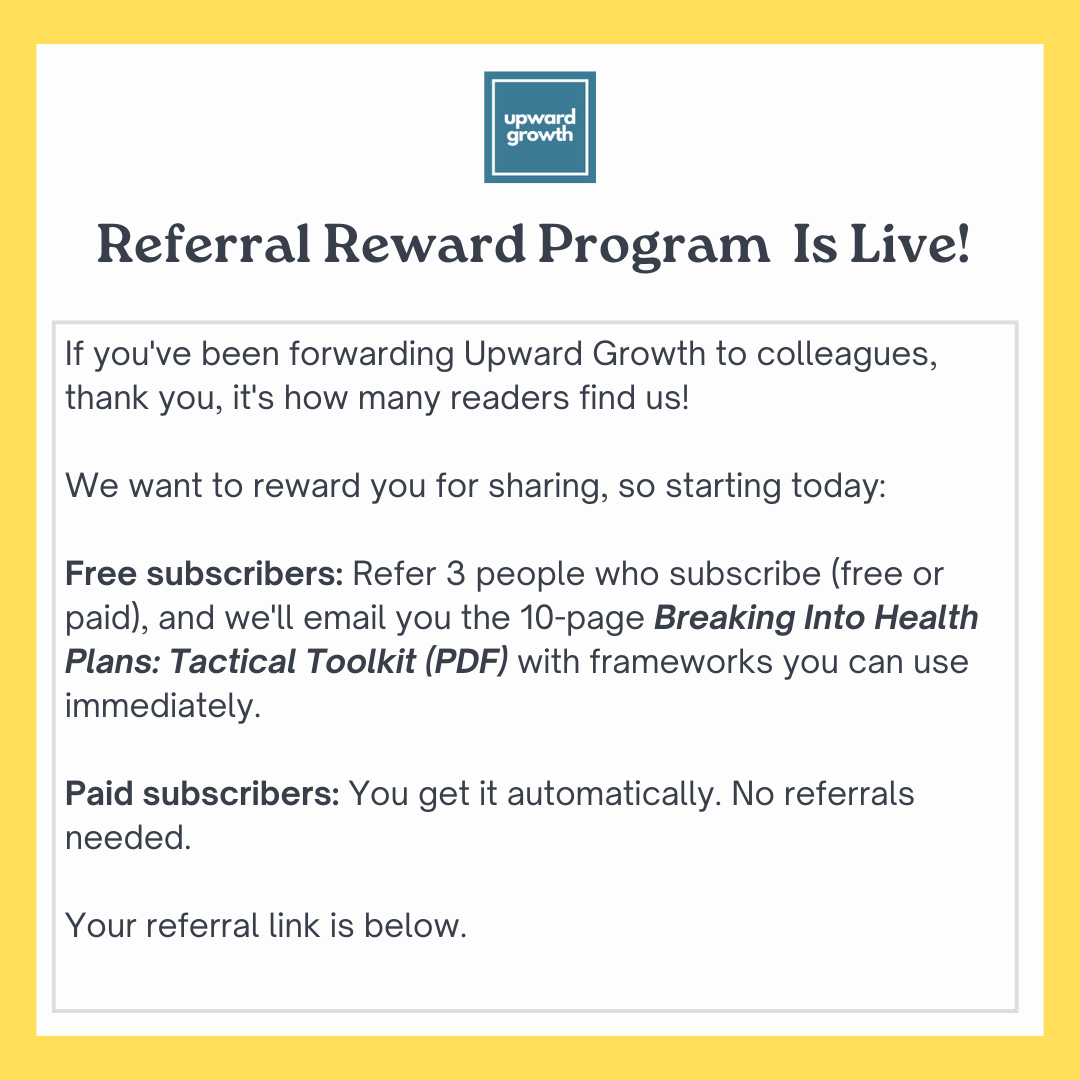

Click the button above to get your personal referral link. When 3 people subscribe using your link, I’ll email you the Tactical Toolkit.